MONDAY, MAY 27, 2019: NOTE TO FILE

Living in the Future's Past

A film on biosphere issues

Eric Lee, A-SOCIATED PRESS

TOPICS: BIOSPHERE AND HUMANITY (SYSTEM) ISSUES, FROM THE WIRES, FILM TRANSCRIPT

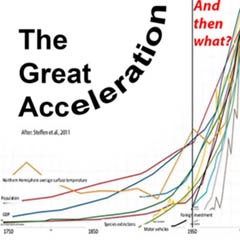

Abstract: Documentaries of interest to those having existential concerns for humanity and the biosphere are as rare as filmmakers who share such concerns, concerns that, among scientists, go back to the Great Acceleration of 1950, at least among the few who could ask, 'And then what?' The film evidences the existence of humans having some grasp of Reality 101 as the narrative told is coherent across minds and not limited to academics or scientist types. Should there ever be a What-is Conference for Real Solutions, most attending (on their own dime, of course) may have letters after their names, but not all. This is cause for hope. The number who might currently attend is small, however (per an ongoing citizen-science project, perhaps 0.001% of the citizens of industrial society would if they could), so few, were they to view the film, would Like or Share the content (apart from the pretty pictures). For the teeming multitudes and their leaders the implications of the what-is are unthinkable, as are real solutions.

COOS BAY (A-P) — This is a transcript of a feature-length 2018 documentary, Living in the Future's Past. I previously spent several days typing a transcript of 'Critical Mass', a documentary with a focus on population issues that included Joseph Tainter, William Rees, Desmond Morris, and Herman Daly with a focus on the science of John B. Calhoun that included 37 others, some of whom, however, made facepalming claims. The film 'Critical Mass', dealing with more important issues, was reviewed by zero film critics and received one award. This new film, with its 'breathtaking wildlife photography' faired better with numerous awards (14) and six reviews by film critics on Rotten Tomatoes, none of whom had the slightest interest nor apparent understanding of what those whose mouths were moving, other than producer/narrator Jeff Bridges, were endeavoring to communicate. Four audience reviews are offered (IMDB has more). Two make coherent comments, but I especially Liked: '90 mins Of random inCohesive stock footages. There were some interesting nuGgets of Wisdom in between too many experts spewing incoherent Academic Phenomenons. This Isnt the movie that is Going to Save the worlD.' That the humor is unintended is what's funny, and this movie definitely isn't going to save the world—I couldn't have said it or evidenced it better.

None say anything to suggest that they are inecolate (not systems science literate to use a Garrett Hardinism). This includes the natural scientists, not too surprisingly, but also the politician/lawyer, philosopher, chief, journalist, psychologists, authors and the general who is exhibit A that 'military intelligence' is not an oxymoron. The content is high value even if the visuals are a distraction. I'm guessing the narration was mostly written by Susan Kucera with input from producer Jeff Bridges. On the whole, with minor quibbles, you can take the content to the bank (the UN's World Reality Bank if and when it opens), or stick it in your pipe and smoke it (way better for you than that other memetic stuff you're smoking). If you don't see, based on your prior research, that virtually every claim is best-guess science, then consider that you may not know enough to have an opinion and should read more books that you'll have plenty of time to read when you stop listening to the sea of prattle that we swim in. And, yes, pretty pictures aside, that includes this film as audiovisual onslaught, but read the transcript and think. 'To think is to listen', but without a pause option, listen to the still small voice in your head as you read the transcript without moving your lips. and 'listen', when not going forth to 'list to Nature's teachings', or to those who listen to Nature.

The 20 Talking Heads:

Bob Inglis, Former Lawyer, Congressman (R) South Carolina, Executive Director Energy and Enterprise Initiative.

Daniel Goleman, Psychologist, Science Journalist, Author, 'Emotional Intelligence'.

Dr. Amy Jacobson, Evolutionary Anthropologist, Human Behavioral, Ecologist, Rutgers University.

Dr. Bruce Hood, Professor of Developmental Psychology, Author, 'The Self Illusion', University of Bristol, UK.

Dr. Joseph Tainter, Professor of Anthropology, Author, 'The Collapse of Complex Societies'.

Dr. Ian Robertson, Cognitive Neuroscientist; Co-Director, Global Brain Health Institute Professor Emeritus, Trinity College Institute of Neuroscience, University of Dublin, Author, 'The Stress Test'.

Dr. Leonard Mlodinow, Physicist, Author, 'Elastic. Flexible Thinking in a Time of Change' and 'The Upright Thinkers'.

Dr. Mark Plotkin, Ethnobotanist, Amazon Conservation Team, Author, 'Tales of a Shaman's Apprentice' and 'Medicine Quest'.

Dr. Nathan Hagens, MBA Finance, PhD Natural Resources, Teaches 'Reality 101 – A Survey of the Human Predicament', University of Minnesota.

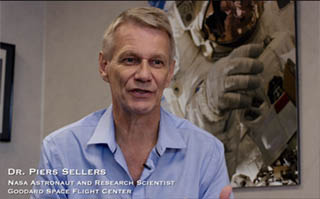

Dr. Peirs Sellers, NASA Astronaut and Research Scientist, Goddard Space Flight Center.

Dr. Renee Lertzman, Psychosocial Science, Author, 'Environmental Melancholia'.

Dr. Rich Pancost, Head of School of Earth Sciences, Professor of Biogeochemistry, Director Cabot Institute, University of Bristol, UK.

Dr. Ruth Gates, Marine Biology, University of Hawaii at Manoa.

Dr. Stephan Lewandowsky, Professor of Cognitive Psychology, University of Bristol, UK.

Dr. Timothy Morton, Philosopher and Author, 'Humankind' and 'Dark Ecology', co-writer of script.

Dr. Ugo Bardi, Professor of Physical Chemistry, University of Florence, Italy, Author, 'The Seneca Effect: Why Growth is Slow but Collapse is Rapid' and 'Extracted: How the Quest for Mineral Resources is Plundering the Planet'.

Jeff Bridges, Narrator, Actor, Artist, Producer.

Oren Lyons, Distinguished Professor of American Studies, Onondaga Council of Chiefs.

Paul Roberts, Journalist, Author, 'End of Oil' and 'The Impulse Society'.

Wesley Clark, General, US Army (Ret.) Former NATO Supreme Allied Commander.

Transcript:

1:18 Narrator, Jeff Bridges, Actor, Artist, Producer:

1:18 Narrator, Jeff Bridges, Actor, Artist, Producer:

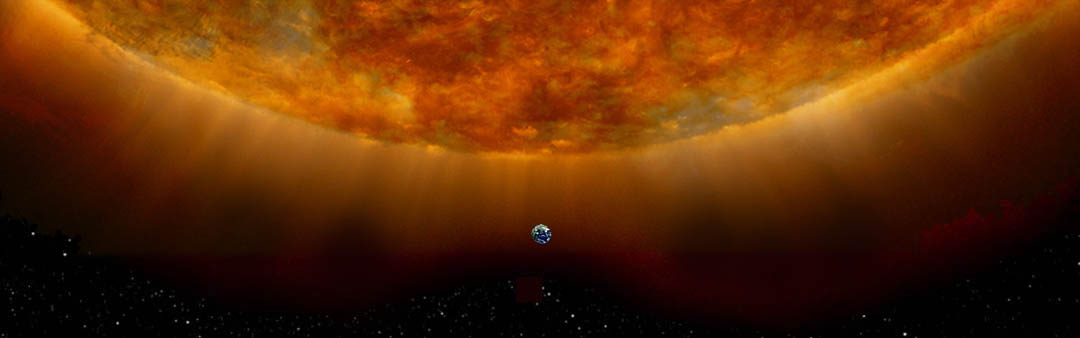

This Earth was here before us, and it will be here long after we are gone. Every living thing on it has evolved together, over eons of time. And although we are part of the web of life, because we see it, we think we stand above it. From all that Nature gave us, we have made a new world out of wilderness, built great civilizations. It seemed there was nothing we could not do. Even the sky itself was not the limit. We see the symptoms of a reality we didn't expect. Have we reached the limitations of our human nature? Is this the end of the line for us? It's hard to tell from our current point of view, living here in the future's past.

2:57 Dr. Peirs Sellers, NASA Astronaut and Research Scientist, Goddard Space Flight Center:

2:57 Dr. Peirs Sellers, NASA Astronaut and Research Scientist, Goddard Space Flight Center:

The world that we live in is just a shockingly blue sphere. When you see it from space, you understand there's a planet that's bowling around the sun, turning on its axis. The oceans, clouds, mountains, forests. You can see it all from up there. You can see over a thousand miles in any direction and it's all moving underneath you at five miles per second. When you look at the horizon, you see a very, very thin little blue ribbon of atmosphere and it really brings home to you...it was a shock to me and I'm a scientist, okay, I thought I had all the scales worked out, intellectually, but it was a shock to me to see how thin the atmosphere is and how obviously it is easily affected by what we do.

3:45 Wesley Clark, General, US Army (Ret.) Former NATO Supreme Allied Commander:

3:45 Wesley Clark, General, US Army (Ret.) Former NATO Supreme Allied Commander:

This is the great challenge of our time dealing with the human impact on the environment and what it means in terms of our civilization going forward.

4:00 Oren Lyons, Distinguished Professor of American Studies, Onondaga Council of Chiefs:

4:00 Oren Lyons, Distinguished Professor of American Studies, Onondaga Council of Chiefs:

We cut all the trees. We kill all the fish. We consume and consume.

4:08 Dr. Timothy Morton, Philosopher and Author, 'Humankind':

4:08 Dr. Timothy Morton, Philosopher and Author, 'Humankind':

So much ecological writing, you know, just open the paper, is about the end of the world. It's starting, when's it going to start, I wonder? Three, two, one, and the concept 'world' as a sort of way of distinguishing between human beings and everything else, has evaporated.

4:28 Bob Inglis, Former Congressman (R) South Carolina, Executive Director Energy and Enterprise Initiative:

4:28 Bob Inglis, Former Congressman (R) South Carolina, Executive Director Energy and Enterprise Initiative:

This is the only place that we know, out of this whole universe, that we can live.

4:37 Dr. Rich Pancost, Professor of Biogeochemistry, Director Cabot Institute, University of Bristol, UK:

4:37 Dr. Rich Pancost, Professor of Biogeochemistry, Director Cabot Institute, University of Bristol, UK:

Life is messy. We are changing multiple aspects of the Earth's environment. Predicting all the effects of it is incredibly complicated.

4:45 Dr. Ruth Gates, Marine Biology, University of Hawaii at Manoa:

4:45 Dr. Ruth Gates, Marine Biology, University of Hawaii at Manoa:

What do we do? We've been standing back and watching Nature decline before our very eyes.

4:52 Dr. Renee Lertzman, Author, 'Environmental Melancholia':

4:52 Dr. Renee Lertzman, Author, 'Environmental Melancholia':

It's on everyone's mind: It's why we are not doing more in response?

4:53 Dr. Leonard Mlodinow, Physicist, Author, 'Environmental Melancholia':

4:53 Dr. Leonard Mlodinow, Physicist, Author, 'Environmental Melancholia':

We've used our abilities to build a huge, technological society that's very advanced. But, in our essence, we're still animals. And one of the problems is that, as animals, we have certain emotions and certain tendencies that are counter-productive in our great, complex society.

5:19 Dr. Bruce Hood, Professor of Developmental Psychology, Author, 'The Self Illusion', University of Bristol, UK:

5:19 Dr. Bruce Hood, Professor of Developmental Psychology, Author, 'The Self Illusion', University of Bristol, UK:

Spinoza, the philosopher, has said, 'Man doesn't understand the unconscious processes which actually really control their conscious behaviors and thoughts'.

5:30 Narrator:

5:30 Narrator:

Perhaps the solutions we are looking for start in us, in our genes, our subconscious motivations, our most primal instincts.

5:42 Dr. Mark Plotkin, Ethnobotanist, Amazon Conservation Team:

5:42 Dr. Mark Plotkin, Ethnobotanist, Amazon Conservation Team:

We are the most flexible species ever evolved, I would think. And when you see people thriving in the Arctic, and you see people thriving in the Kalahari Desert, and you see people thriving in the Amazon Rainforest, these are titanic accomplishments. But, we also have the ability to destroy all of those habitats, and everything in between.

6:11 Narrator:

Can looking at evolution help us understand the current conscious-self we have and the future of humanity?

6:26 Dr. Amy Jacobson, Evolutionary Anthropologist, Human Behavioral, Ecologist, Rutgers University:

6:26 Dr. Amy Jacobson, Evolutionary Anthropologist, Human Behavioral, Ecologist, Rutgers University:

From an evolutionary perspective humans are just another species. We're unique, but evolutionary biology sees every species as unique.

6:38 Dr. Mark Plotkin, Ethnobotanist, Amazon Conservation Team:

6:38 Dr. Mark Plotkin, Ethnobotanist, Amazon Conservation Team:

Every species, everywhere, is a genius at survival, otherwise it wouldn't be here. Every species can teach us something.

6:48 Dr. Bruce Hood, Professor of Developmental Psychology, Author, 'The Self Illusion', University of Bristol, UK:

6:48 Dr. Bruce Hood, Professor of Developmental Psychology, Author, 'The Self Illusion', University of Bristol, UK:

When you look at all the different lifeforms, the plants and the animals, they just seem so different to each other. But, of course, we're all made of the same stuff. The atoms, which make the molecules, which produced the DNA. And the diversity started this process of natural selection. So, we know that natural selection has allowed diversity to appear as a process of winning out those who are most suited to the environments.

7:11 Dr. Ruth Gates, Marine Biology, University of Hawaii at Manoa:

7:11 Dr. Ruth Gates, Marine Biology, University of Hawaii at Manoa:

Natural selection has evolved different lineages of organisms, and we are at the top of one of those lineages.

7:21 Dr. Timothy Morton, Philosopher and Author, 'Humankind':

7:21 Dr. Timothy Morton, Philosopher and Author, 'Humankind':

That there are other animals doesn't mean that underneath our sophisticated civilization we are these utilitarian lumps. It's exactly the opposite. What it means is that being sophisticated and artistic goes all the way down and leads to the level of beetles with iridescent wing cases. Because there's something intrinsically non-utilitarian and playful about evolution.

7:46 Oren Lyons, Distinguished Professor of American Studies, Onondaga Council of Chiefs:

7:46 Oren Lyons, Distinguished Professor of American Studies, Onondaga Council of Chiefs:

We're part of the system. We're Nature. We're part of the Earth, and we're fundamentally dependent on its good graces; every symbiotic relationship to everything on this Earth.

7:57 Bob Inglis, Former Congressman (R) South Carolina, Executive Director Energy and Enterprise Initiative:

7:57 Bob Inglis, Former Congressman (R) South Carolina, Executive Director Energy and Enterprise Initiative:

I understand some people if they say, 'No, no, this is a science thing, it's not for us. That's the province of God, we shouldn't go there'. I can hear that view, but I, I really don't think it's what I see in scripture. What I see in scripture is, 'C'mon, I want to show it to you. I want to reveal myself to you'. I don't see science as challenging my faith. In fact, I see it as affirming my faith.

8:34 Dr. Ruth Gates, Marine Biology, University of Hawaii at Manoa:

8:34 Dr. Ruth Gates, Marine Biology, University of Hawaii at Manoa:

We are new on the planet. We are the most newly evolved. We are a trial run.

8:42 Dr. Amy Jacobson, Evolutionary Anthropologist, Human Behavioral, Ecologist, Rutgers University:

8:42 Dr. Amy Jacobson, Evolutionary Anthropologist, Human Behavioral, Ecologist, Rutgers University:

In terms of evolution, animals adapt to their ecological conditions. But as humans, we have been able to control our ecological conditions. Evolution itself is a process by which organisms become more efficient at extracting resources from their environment. Humans are unique, and that what makes us so different from all other animals is our mastery of technology. We're uniquely able to transform our environment in ways no other animals can.

9:14 Narrator:

We humans are really big-brained primates that lucked out by becoming bi-pedal and discovering how to coerce other animals from a distance, by being able to throw. We figured out how to tame fire and use it to our advantage. Our evolving technology allowed us to expand into new territories and manipulate the environment in ways that gave us an edge.

9:46 Dr. Bruce Hood, Professor of Developmental Psychology, Author, 'The Self Illusion', University of Bristol, UK:

9:46 Dr. Bruce Hood, Professor of Developmental Psychology, Author, 'The Self Illusion', University of Bristol, UK:

Places like this remind me about how harsh Nature can be. We're so used to living in air conditioning and having the comfort of the modern world. But when you go out into Nature, and experience it firsthand, you're reminded very powerfully about how weak we are as an animal.

10:04 Narrator:

And this is because we are fundamentally a cultural species. Culture is our life support system [no, it isn't]. Our cumulative culture allows us to cushion ourselves against the harsh realities of the environment [no, it doesn't] and to reshape the environment [using energy and technology]. Our culture is an integral part of our ecology. We can trace human ancestors back over 4 million years, and anatomically modern humans for more than 200,000 years. And we have inherited their successful survival traits. These traits are in all of us, to some extent, traits like optimizing time, really caring about what other people think about us [social approbation, e.g. social media], and comparing ourselves to others. We are still trying to attain the same daily emotional state as our successful ancestors. We carry the same neurotransmitters in our brains that created the exhilarating feeling our ancient ancestors got when they had the unexpected reward of finding a berry, or a nut, or were looking forward to a successful hunt. But in a culture of amazing technology, we are surrounded by ready-made stimuli pushing us to reward ourselves. Our evolutionary impulses can be easily hijacked.

11:44 Dr. Bruce Hood, Professor of Developmental Psychology, Author, 'The Self Illusion', University of Bristol, UK:

11:44 Dr. Bruce Hood, Professor of Developmental Psychology, Author, 'The Self Illusion', University of Bristol, UK:

Irrespective of where you grew up, it's in our DNA to copy those around us. For humans, imitation is part and parcel of what it is to be a member of a tribe.

11:55 Narrator:

Now our adaptations are primarily to the cultural environment we created around us. If we don't fit into our culture, we're not going to reproduce, we're not going to survive very well. We're going to be ostracized, and being ostracized in a social species like ours can feel like a death sentence. Do we have a human brain mismatched between how we evolved to be here, and the modern circumstances we find ourselves in? Are our needs any different from our ancestors?

12:32 Dr. Timothy Morton, Philosopher and Author, 'Humankind':

12:32 Dr. Timothy Morton, Philosopher and Author, 'Humankind':

Need, the word, can mean strongly desired like, can;t it, 'I really need a bar of chocolate' and I'm afraid to say that from my point of view, I'm sure Neanderthals would have totally loved Coca Cola Zero. They looked really good and pure because they didn't have it, you know, it's us poor saps, but presumably they got the same nervous system. If it's true that Neanderthals would have also become addicted to Angry Birds, there's something true in contemporary society. Contemporary society is saying something true about ancient people.

13:06 Dr. Bruce Hood, Professor of Developmental Psychology, Author, 'The Self Illusion', University of Bristol, UK:

13:06 Dr. Bruce Hood, Professor of Developmental Psychology, Author, 'The Self Illusion', University of Bristol, UK:

This is a modern human brain, and as far as we can tell it's identical to the brain of individuals who lived fifty thousand years ago. But, of course, the information which is stored in the modern brain is very different to that of our ancestors. The brain basically encodes information and that information will change from one generation to the next. So, you can see the course of human evolution as the accumulation of wisdom and knowledge that we pass on from one generation to the next.

13:42 Daniel Goleman, Psychologist, Science Journalist, Author, 'Emotional Intelligence':

13:42 Daniel Goleman, Psychologist, Science Journalist, Author, 'Emotional Intelligence':

Our perceptual system isn't attuned to the massive changes that are happening on the planet, nor are they attuned to the very fine-grained details of those changes. Our brain's alarm system for threat, the amigdyla, the emotional centers, are very tuned to these earlier dangers from a time when that rustle in the bushes might be a tiger that was about to eat you or today's symbolic realities, 'I'm not being treated fair', or, 'Honey, we have to talk', or whatever it is that triggers you.

14:20 Dr. Stephan Lewandowsky, Professor of Cognitive Psychology, University of Bristol, UK:

14:20 Dr. Stephan Lewandowsky, Professor of Cognitive Psychology, University of Bristol, UK:

We have a very quick system that is sort of dealing with gut reactions, with reflex responses, with an instant response to danger. And on the other hand, we have a slower more deliberative system, which takes time to engage, and which is slow and ponderous, that we should keep engaged when we're looking at complex issues in the world around us.

14:55 Narrator:

We are physical and biological beings living in an ocean of cosmic energy. That sounds pretty trippy [New Agey], and it is. Where every part contains information about the whole. The long view is both forward and back.

15:27 Dr. Amy Jacobson, Evolutionary Anthropologist, Human Behavioral, Ecologist, Rutgers University:

15:27 Dr. Amy Jacobson, Evolutionary Anthropologist, Human Behavioral, Ecologist, Rutgers University:

For 99.9% of our evolutionary history, we were hunting and gathering people, living in small kin groups where everybody was related to everybody and therefore, we had a vested interest in taking care of each other. We also lived off of the land in such a way that we did not live beyond the carrying capacity of the environment. There was no way to store food for long periods of time, and therefore, there was no ability to acquire surplus. What this resulted in is that it created a very egalitarian social system where women had autonomy, there was no real rigid dominance hierarchy among men, and it was only after the invention of agriculture and the domestication of plants and animals that humans were faced with the situation of what to do with these surplus resources.

16:23 Narrator:

This was the beginning of the Neolithic Revolution. We started farming for the first time. Everything took off from there, and that's only been around 12,000 years. That's a blink of an eye, in evolutionary terms. Controlling the production and distribution of these surplus resources led to a change in human cultural and social organization. Cultural evolution is a transferable system a lot like DNA. It has all the properties of an evolving system.

17:02 Dr. Nathan Hagens, MBA Finance, PhD Natural Resources, Teaches 'Reality 101 – A Survey of the Human Predicament', University of Minnesota:

17:02 Dr. Nathan Hagens, MBA Finance, PhD Natural Resources, Teaches 'Reality 101 – A Survey of the Human Predicament', University of Minnesota:

Since we found agriculture, things changed. And we, we started to act like a larger entity just like an ant colony, or a termite colony, or a beehive.

17:22 Narrator:

17:22 Narrator:

Bees and ants are individual organisms performing different roles. They rush about to feed or defend the colony and collectively they create a superorganism. Of course, humans are not social insects, but if you were able to watch a village or a city from a distance over time, it looks a lot like a growing interdependent superorganism; a reorganization of material existence with far reaching implications.

18:00 Dr. Joseph Tainter, Professor of Anthropology, Author, 'The Collapse of Complex Societies':

18:00 Dr. Joseph Tainter, Professor of Anthropology, Author, 'The Collapse of Complex Societies':

Today we live in a world of material abundance and inexpensive energy. And this leads us to think that this is normal for humans, that it's the normal human condition. Early societies, even through the middle ages, and up until almost the modern era had 90% of their economies devoted to the production of energy, primarily in the form of food. That meant that 90% of what people did involved producing energy. In other words, just getting by.

18:35 Narrator:

Our lives were based on the solar flows. Sunlight hit the earth, photosynthesis grew the plants, rain and soil with the nutrients grew crops, animals ate the crops, and we ate the animals. Energy transforms from one state to another. Our bodies were products of the current sunlight of the day.

19:05 Dr. Ugo Bardi, Professor of Physical Chemistry, University of Florence, Italy:

19:05 Dr. Ugo Bardi, Professor of Physical Chemistry, University of Florence, Italy:

And they're just transient entities which appear, move a little bit, and then disappear. That's the way the system works. And, we have this chance to be alive, to move on this planet, to do things on this planet, to create things on this planet, because we have this gigantic flux of energy coming from the sun. The whole universe is a giant machine for dispersing energy potential. Energy is everything in the sense that nothing moves in the universe without an energy potential development. We have been also able to increase this already very large amount of energy by means of using ancient processes frozen below the ground in the Earth's crust in the form of what we call fossil fuels.

20:16 Narrator:

Fossil sunlight is so powerful it's indistinguishable from magic. And we're mining this ancient sunlight in a very brief period of human history.

20:35 Dr. Nathan Hagens, MBA Finance, PhD Natural Resources, Teaches 'Reality 101 – A Survey of the Human Predicament', University of Minnesota:

20:35 Dr. Nathan Hagens, MBA Finance, PhD Natural Resources, Teaches 'Reality 101 – A Survey of the Human Predicament', University of Minnesota:

A chemical composition of 50% of the protein in our bodies, and 80% of the nitrogen in our bodies indirectly comes from the chemical signature of this fossil sunlight that we're mining. So, we are different than our ancestors. They were made of sunlight, we are made of fossil fuels.

20:57 Dr. Joseph Tainter, Professor of Anthropology, Author, 'The Collapse of Complex Societies':

20:57 Dr. Joseph Tainter, Professor of Anthropology, Author, 'The Collapse of Complex Societies':

In hunting and gathering societies solar energy can provide enough food to support maybe one person per square mile. Basic subsistence agriculture can support more people, but nowhere near the population densities that we have today. The way we live is an anomaly.

21:20 Paul Roberts, Journalist, Author, 'The Impulse Society':

21:20 Paul Roberts, Journalist, Author, 'The Impulse Society':

So, there's really no way for anyone to know, at a sort of a visceral level, that there are any problems with the system, and if you look around, it all works. We know historically, to the extent that we pay attention to it, we used to use wood. We're sort of aware that our predecessors used wood and they used so much of it they had to switch to something else. They switched to coal. And then they switched to oil.

21:52 Dr. Nathan Hagens, MBA Finance, PhD Natural Resources, Teaches 'Reality 101 – A Survey of the Human Predicament', University of Minnesota:

21:52 Dr. Nathan Hagens, MBA Finance, PhD Natural Resources, Teaches 'Reality 101 – A Survey of the Human Predicament', University of Minnesota:

Eighty years ago, the oil in America was just under the surface. We would need very little machinery to get these gusher wells and we would get out over 100 times the energy that we put in. Suddenly this whole new world of transportation opened up, and with that, this entirely new model for how we fed ourselves, how we clothed ourselves and built shelter, and it totally changed the way we live. It made it possible for us to move away from the country. Throughout human history, we had to live sort of scattered in order to not tax any particular resource too greatly. As we began to be able to import food, or import energy, we could pretty much live where we wanted to, and where we wanted to live was in the cities. So, we have this massive migration, and we empty the countryside. We all move to the city because we grow food in the country and we can just transport it to the city, and once you're in the city then you can do all these other things. You can create all this knowledge, you can create technologies, you can create this massive economic growth, and the longer you've been living that way, the harder it is to remember what allowed it to start in the first place, and that was this idea of cheap energy. Humans gradually became a functional [actually dysfunctional] superorganism. At first, we would maximize grain surplus. We would grow more grain and store it, and that would allow our population to increase and our territory to expand. But now we're maximizing surplus value. We're maximizing financial, digital, electronic representations of surplus. But all money really effectively is, is a claim on some energy services. And so what ends up happening is money, trade, technology are all in service of the superorganism.

24:20 Narrator:

It's nearly impossible for individuals to function independently in modern society. We contribute to and rely on a growing superorganism to feed us, clothe us, power our sophisticated communications, even protect our societies from each other through highly organized warfare. We live within a mesh of energy-eating interdependence and we never really see the big picture. A state of plenty can have unintended consequences. It is the paradox of our times.

25:02 Dr. Timothy Morton, Philosopher and Author, 'Humankind':

25:02 Dr. Timothy Morton, Philosopher and Author, 'Humankind':

Running in the background of all that we do, whether we consider ourselves to be capitalist, or soviet, or feudal, or everything, is a kind of program, a kind of recipe, a kind of algorithm, the logistical functioning of Neolithic society, which started all over the world. The trouble is that when you wash, rinse, repeat; eventually, when you do it enough times, it starts to reveal its flaws. For example, me starting my car is statistically meaningless from a global warming point of view. Billions and billions of car ignition turnings has a meaning, and that's the paradox. All of a sudden, we realize that we're part of a superorganism.

25:41 Daniel Goleman, Psychologist, Science Journalist, Author, 'Emotional Intelligence':

25:41 Daniel Goleman, Psychologist, Science Journalist, Author, 'Emotional Intelligence':

We are enmeshed in systems of production, systems of manufacture, systems of use.

25:50 Dr. Renee Lertzman, Author, 'Environmental Melancholia':

25:50 Dr. Renee Lertzman, Author, 'Environmental Melancholia':

It's incredibly important to recognize that we're all part of the system.

26:00 Dr. Leonard Mlodinow, Physicist, Author, 'Environmental Melancholia':

26:00 Dr. Leonard Mlodinow, Physicist, Author, 'Environmental Melancholia':

As social organisms we're something like ants. Our signals that we exchange are far more complicated than the simple chemical signals that ants exchange, but we do exchange signals, and as humans, we take individual actions that, on the whole, cause emergent behavior. The problem with this happening today is that the emergent behavior is growing very complex and detrimental to the planet, to ourselves, and to many other species.

26:33 Narrator:

Emergent behavior is all around us. It could be fast moving and unpredictable. No one could foresee our patterns of interaction would lead to the internet, the smart phone, the disappearance of phone booths, and the rise of server farms. Who knows what will happen next?

26:58 Bob Inglis, Former Congressman (R) South Carolina, Executive Director Energy and Enterprise Initiative:

26:58 Bob Inglis, Former Congressman (R) South Carolina, Executive Director Energy and Enterprise Initiative:

We're all in this together. Maybe if you're off the grid and truly walking everywhere you go, maybe then you have the right to polish your halo.

27:07 Wesley Clark, General, US Army (Ret.) Former NATO Supreme Allied Commander:

27:07 Wesley Clark, General, US Army (Ret.) Former NATO Supreme Allied Commander:

We're tiny little microbes on the surface of this huge planet. We can actually affect the planet and cause it to respond.

27:27 Dr. Peirs Sellers, NASA Astronaut and Research Scientist, Goddard Space Flight Center:

27:27 Dr. Peirs Sellers, NASA Astronaut and Research Scientist, Goddard Space Flight Center:

If we don't stop emitting carbon dioxide at these rates, pretty soon we're going to be in trouble. We're going to have massive climatic disruption. The rainfall belts will move. People in the hundreds of millions, maybe a billion and a half people will have problems getting access to fresh water and food.

27:55 Dr. Rich Pancost, Professor of Biogeochemistry, Director Cabot Institute, University of Bristol, UK:

27:55 Dr. Rich Pancost, Professor of Biogeochemistry, Director Cabot Institute, University of Bristol, UK:

The issue is not what the world is like when it's cold or when it's warm. We are in a time of change. What is interesting is how the world changes when you dramatically, in our case, increase the concentration of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases in the atmosphere. Or, when it suffers mammoth biodiversity loss caused by our own behavior. If there's a big change coming, and we want to know what it might do in the future, what do we do? We look at what's happened in the past. Geological history largely reinforces the lessons from the climate models. When they say the doubling of carbon dioxide will lead to about 2.5 degrees to 3 degrees of warming, the history of the Earth is broadly in agreement with that. So, a lot of my own research is focused on the reconstruction of past climate. We look at dramatic transitions. And, there's not a lot of those, because in Earth history, things change gradually. Three years ago, I started on a project. It was to look at an event that was about 120 million years ago. And it was to explore exactly this: it was what we generally consider a rapid ocean acidification event, a rapid warming event, and we thought, 'Let's look at this, and see what happened'. And as we studied it more and more, and we got better and better at age models, we got better and better reconstructions of the climate change. It became apparent that this particular event that happened about 100 million years ago, the climate change happened over about 40,000 years. This is the same degree of climate change that we think might happen over the next 100 years [400x faster]. There's much more energy in the system. We have very little knowledge of how Earth's biological life support systems will respond to dramatic and rapid change.

29:58 Dr. Ruth Gates, Marine Biology, University of Hawaii at Manoa:

29:58 Dr. Ruth Gates, Marine Biology, University of Hawaii at Manoa:

We have extraordinary biomes on the planet that all are individual pieces of a jigsaw. The picture is clear when they all function, and are all present, but start picking those pieces off and you can no longer see, really, what that picture looks like and the functionality of the entire system is out of whack.

30:36 Dr. Peirs Sellers, NASA Astronaut and Research Scientist, Goddard Space Flight Center:

30:36 Dr. Peirs Sellers, NASA Astronaut and Research Scientist, Goddard Space Flight Center:

The Arctic icecap is shrinking. The Greenland ice mass is being lost at 300 gigatons per year. Three hundred cubic kilometers of ice per year is disappearing. The ocean is changing. Sea level rise, we're seeing significant sea level rise. We're expecting a couple of feet, maybe more before the end of the century. So, all these things are facts. It's not so much the change itself, but it's how fast it's happening.

31:05 Dr. Rich Pancost, Professor of Biogeochemistry, Director Cabot Institute, University of Bristol, UK:

31:05 Dr. Rich Pancost, Professor of Biogeochemistry, Director Cabot Institute, University of Bristol, UK:

The faster the change comes, the less time we have to adapt. The faster the change comes, the less time the trees have to adapt, or plankton living in the ocean. The faster the change comes, the less time ecosystems have to adapt. And the more complex these are, the harder it is to actually predict what the consequences of that change will be.

31:28 Dr. Peirs Sellers, NASA Astronaut and Research Scientist, Goddard Space Flight Center:

31:28 Dr. Peirs Sellers, NASA Astronaut and Research Scientist, Goddard Space Flight Center:

Climate change is going to put huge stress on societies that are already under internal political stress and, stress induced by lack of resources.

31:41 Dr. Rich Pancost, Professor of Biogeochemistry, Director Cabot Institute, University of Bristol, UK:

31:41 Dr. Rich Pancost, Professor of Biogeochemistry, Director Cabot Institute, University of Bristol, UK:

Like, food availability, water availability, dramatic events associated with climate change, all of which potentially will exacerbate the divisions within society. Access to wealth creates divisions. Access to food and water makes the divisions very pronounced.

32:00 Wesley Clark, General, US Army (Ret.) Former NATO Supreme Allied Commander:

32:00 Wesley Clark, General, US Army (Ret.) Former NATO Supreme Allied Commander:

It's going to impact the way humans live on the planet. And when that impacts, then people move. People are angry. Land becomes less valuable, or more valuable. Populations shifts, and those shifts destabilize governments.

32:25 Narrator:

We might look up at night and wonder at the far away stars as if we were in a pristine crystal snow globe. But our problems can no longer be pushed into the backyard of the less powerful, the less fortunate among us. No. Here we are, and here we were made. Where everything from farmers, dogs, LED lights, flowers, pencils, politicians, microwaves, and penguins, the past, present, and future are all interrelated.

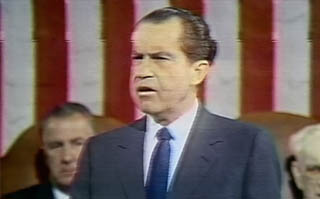

33:15 President Richard Nixon 1970:

33:15 President Richard Nixon 1970:

In the next ten years, we shall increase our wealth by fifty percent. The profound question is 'Does this mean we will be fifty percent richer, in a real sense, fifty percent better off, fifty percent happier?'

33:34 Dr. Nathan Hagens, MBA Finance, PhD Natural Resources, Teaches 'Reality 101 – A Survey of the Human Predicament', University of Minnesota:

33:34 Dr. Nathan Hagens, MBA Finance, PhD Natural Resources, Teaches 'Reality 101 – A Survey of the Human Predicament', University of Minnesota:

And so, to just get more facts about climate change or about oil depletion, or about environmental destruction, people don't know what to do, because they're part of this organism trying to get more feel-good brain chemicals.

33:51 Dr. Ruth Gates, Marine Biology, University of Hawaii at Manoa:

33:51 Dr. Ruth Gates, Marine Biology, University of Hawaii at Manoa:

The treadmill is getting smaller and smaller and smaller and smaller; and the number of people who want to be on the treadmill is getting bigger and bigger and bigger and bigger. And eventually, there's going to be no room to run. And so, people will fall off. Many people will fall off.

34:11 Dr. Renee Lertzman, Author, 'Environmental Melancholia':

34:11 Dr. Renee Lertzman, Author, 'Environmental Melancholia':

We are profoundly motivated by having purpose. We're motivated by having a sense of autonomy, efficacy, and control. Where it seems that our gifts, our energy, our life force is not going to have some impact, we will simply withdraw and we will very likely redirect that energy into where we can feel we have most impact. And where is that in our culture right now? It's in consumption.

34:47 Dr. Mark Plotkin, Ethnobotanist, Amazon Conservation Team:

34:47 Dr. Mark Plotkin, Ethnobotanist, Amazon Conservation Team:

The economist Immanuel Wallerstein has talked about world systems theory, in which all things are connected for better, and often for worse. So, living here in the most industrialized part of the industrialized world, our tentacles reach everywhere.

35:10 Narrator:

Efficacy is the ability to produce a desired result. But are the results we're achieving, the ones we intend? Wild animals are disappearing forever. Our intelligence is remaking the world before our eyes.

35:28 Dr. Leonard Mlodinow, Physicist, Author, 'Environmental Melancholia':

35:28 Dr. Leonard Mlodinow, Physicist, Author, 'Environmental Melancholia':

Today we can just click on a link somewhere and have something appear at our doorstep without having any idea of what went into getting it there. All we know about what got it there is the price. We get more and more detached from the actual cost of creating and transporting what we're using. Energy is really at the center of physics, but for the layperson, probably the easiest way to explain it is that energy is the ability to do work. Work is force through distance. So, every time you move something, from China to the U.S. or from the floor to the ceiling, that takes energy. When you drive to work, obviously it takes energy. To boil one quart of water, takes up the equivalent of 500 calories of food. Any kind of transformation requires energy.

36:23 Dr. Ugo Bardi, Professor of Physical Chemistry, University of Florence, Italy:

36:23 Dr. Ugo Bardi, Professor of Physical Chemistry, University of Florence, Italy:

We are powerful creatures on this planet, but we still need the ecosystem to survive. So we don't want to destroy the ecosystem, because it would be rather bad. And this is a transition, you can call it also a revolution, you can call it whatever you'd like. The point is that there have been such revolutions, such transitions in the past, but these transitions have a cost. An energy transition must be paid in energy.

36:54 Narrator:

36:54 Narrator:

Energy is the currency of life. Energy creates movement and food. All life taps energy flows. We used to measure units of energy in terms of horsepower. One horse could do the work of ten men. A small tractor could do the work of forty horses. It would take 450 horses or more to get the same work done as just one semi-truck. And unlike horses, trucks can work day and night, in any weather. The flow of fossil fuel has turbo-charged our society.

38:00 Dr. Nathan Hagens, MBA Finance, PhD Natural Resources, Teaches 'Reality 101 – A Survey of the Human Predicament', University of Minnesota:

38:00 Dr. Nathan Hagens, MBA Finance, PhD Natural Resources, Teaches 'Reality 101 – A Survey of the Human Predicament', University of Minnesota:

So, to just say we have the science now to realize that these fossil slaves, they don't complain, they don't sleep, they're tireless, they're super strong, but they poop and they breathe, and their breath is causing our biosphere to warm up, and our oceans to acidify. Let's keep them in the ground? It's not quite so simple. If you consider the power that's in fossil fuels, ninety percent of the work done in human economies is done by fossil slaves. The average American consumes 220,000 kilocalories, every day. We don't think about that, we only think about the 3,000 or 3,500 of food that we eat. But our energy footprint is almost 100 times more than that, if you consider our buses, and our airplanes, and all the hospitals, and the Disneylands, and the NASCARs, and in all the various things that we buy that are imported all around the world.

39:09 Wesley Clark, General, US Army (Ret.) Former NATO Supreme Allied Commander:

39:09 Wesley Clark, General, US Army (Ret.) Former NATO Supreme Allied Commander:

It's what people invest in, and a lot of pension funds, and a lot of the institutions that so much of humanity depends on - of course they gravitate toward oil.

39:18 Dr. Nathan Hagens, MBA Finance, PhD Natural Resources, Teaches 'Reality 101 – A Survey of the Human Predicament', University of Minnesota:

39:18 Dr. Nathan Hagens, MBA Finance, PhD Natural Resources, Teaches 'Reality 101 – A Survey of the Human Predicament', University of Minnesota:

Renewable energy, although it's mature and it's getting very cheap, it's not going to replace this infrastructure, and this civilization. We have a very limited amount of time to transition to a low-carbon economy, but it's very naive to just say, let's keep it in the ground and keep everything else running.

39:42 Dr. Ugo Bardi, Professor of Physical Chemistry, University of Florence, Italy:

39:42 Dr. Ugo Bardi, Professor of Physical Chemistry, University of Florence, Italy:

'So if you ask 'can solar energy power our society as it is today?' Then you already have the answer. It is 'no': it is not possible. If you want to switch from oil and gas and coal and to move to solar energy, then you have to change a lot of things.

39:58 Dr. Nathan Hagens, MBA Finance, PhD Natural Resources, Teaches 'Reality 101 – A Survey of the Human Predicament', University of Minnesota:

39:58 Dr. Nathan Hagens, MBA Finance, PhD Natural Resources, Teaches 'Reality 101 – A Survey of the Human Predicament', University of Minnesota:

Our food system right now is an energy sink. We use 10 to 12 fossil-calories to produce 1 food-calorie. Right now, we have around 100 trillion dollars worth of machinery on the planet that uses gasoline or diesel fuel. So, for one barrel of oil, which we pay $50 for, we have thousands of fossil slaves standing behind us.

40:28 Wesley Clark, General, US Army (Ret.) Former NATO Supreme Allied Commander:

40:28 Wesley Clark, General, US Army (Ret.) Former NATO Supreme Allied Commander:

The American inventory of automobiles, 250 - 270 million cars and light trucks on the road, you're talking about more than a decade of production and you're talking about more wealth than the gross domestic product in a year to replace it. So, you're not going do these, make these changes over night.

40:50 Dr. Ugo Bardi, Professor of Physical Chemistry, University of Florence, Italy:

40:50 Dr. Ugo Bardi, Professor of Physical Chemistry, University of Florence, Italy:

You see, there is a parameter which is very basic in evaluating these kinds of things, which is called energy return on energy invested.

40:58 Dr. Nathan Hagens, MBA Finance, PhD Natural Resources, Teaches 'Reality 101 – A Survey of the Human Predicament', University of Minnesota:

40:58 Dr. Nathan Hagens, MBA Finance, PhD Natural Resources, Teaches 'Reality 101 – A Survey of the Human Predicament', University of Minnesota:

Energy doesn't cost dollars. I mean, it does, but it really costs energy.

41:03 Wesley Clark, General, US Army (Ret.) Former NATO Supreme Allied Commander:

41:03 Wesley Clark, General, US Army (Ret.) Former NATO Supreme Allied Commander:

Oil's the biggest industry on the planet. So, it sets the pace, in terms of inflation. So, if you raise the price of oil, all the other prices go up, until people have accommodated, and they can still afford to buy, pay the extraction cost for oil.

41:20 Dr. Nathan Hagens, MBA Finance, PhD Natural Resources, Teaches 'Reality 101 – A Survey of the Human Predicament', University of Minnesota:

41:20 Dr. Nathan Hagens, MBA Finance, PhD Natural Resources, Teaches 'Reality 101 – A Survey of the Human Predicament', University of Minnesota:

So, it's not like we're running out of oil, or coal or gas, it's that it's getting more costly, in energy terms, to get it. Because it's more costly, it has less benefits to the rest of society. The 1930's, the Beverly Hillbilly oil just bubbling under the ground? We've used all that. Net energy, which is the energy left after we pay the energy cost of finding and extracting it, net energy is declining now. We don't realize the scale and the stakes of what's happening.

41:58 Dr. Joseph Tainter, Professor of Anthropology, Author, 'The Collapse of Complex Societies':

41:58 Dr. Joseph Tainter, Professor of Anthropology, Author, 'The Collapse of Complex Societies':

When we take on debt, we are promising to repay it, with future energy. The fossil fuels will not last forever, they cannot last forever.

42:08 Dr. Nathan Hagens, MBA Finance, PhD Natural Resources, Teaches 'Reality 101 – A Survey of the Human Predicament', University of Minnesota:

42:08 Dr. Nathan Hagens, MBA Finance, PhD Natural Resources, Teaches 'Reality 101 – A Survey of the Human Predicament', University of Minnesota:

The energy potential in one barrel of oil is equal to a human being working 40 hours a week for four and a half years.

42:19 Dr. Ugo Bardi, Professor of Physical Chemistry, University of Florence, Italy:

42:19 Dr. Ugo Bardi, Professor of Physical Chemistry, University of Florence, Italy:

You have to think for the future, you have to save something for the future in order to have a harvest of renewable energy. 'Do not eat your seed corn', is an old saying.

42:40 Narrator:

Wise farmers know that if they eat their seed corn there will be nothing left to plant for future harvest. Will future generations look back at today and view much of the energy we're burning to have been wasted? Are we eating our seed corn? So many of us have come to expect the level of comfort and convenience unprecedented in our biological past. We need to redefine our expectations. Not as what we will lose, but what we might gain, by preparing for something different.

43:28 Dr. Nathan Hagens, MBA Finance, PhD Natural Resources, Teaches 'Reality 101 – A Survey of the Human Predicament', University of Minnesota:

43:28 Dr. Nathan Hagens, MBA Finance, PhD Natural Resources, Teaches 'Reality 101 – A Survey of the Human Predicament', University of Minnesota:

'Oh, fossil fuels are bad? We need to keep them in the ground.' So, we've got this big divestment campaign where we stop investing in coal and oil and natural gas. But if we stop investing in the stocks, as long as we continue to fly and drive and have infrastructure built around cheap transportation and global connectivity of supply chains, then some hedge fund will just buy those stocks back, 5 cents cheaper.

43:56 Dr. Timothy Morton, Philosopher and Author, 'Humankind':

43:56 Dr. Timothy Morton, Philosopher and Author, 'Humankind':

We can very easily get into the mode, for example when we think about oil, of addiction speech. 'I'm going to leave this bottle of whiskey in the cupboard, and I'm not going to touch a drop of it.' Which means that I'm still fixated on this whiskey. Paradoxically, this is actually, of course, not really thinking differently. There's a bit of a hangover from this myth that things should be functioning smoothly and that smooth functioning is something that's real.

44:35 Paul Roberts, Journalist, Author, 'The Impulse Society':

44:35 Paul Roberts, Journalist, Author, 'The Impulse Society':

If you find yourself ten or twenty years from now, in a world where energy isn't cheap, you're going to have to unwind, somehow, this massive global city system. You look back in history to times when this happened before, I mean, the Roman Empire, one of the reasons it fell was it was no longer able to continue to bring in food and supplies to Rome and the other big city-states, and cities no longer were habitable. They just didn't function anymore. So, what happens this time around?

45:11 Wesley Clark, General, US Army (Ret.) Former NATO Supreme Allied Commander:

45:11 Wesley Clark, General, US Army (Ret.) Former NATO Supreme Allied Commander:

And in the past, it's been conflict with other tribes that has brought human 'progress', such as it is, at a tremendous cost of slaughter. World War I brought forth radio and airplanes. World War II gave us nuclear energy. Space race between the United States and the Soviet Union and the Cold War that gave us communication satellites and global positioning and many other things, and now we're where we have to work collectively. We can't work against each other, we have to work with each other, we have to work with each other with the view of the future, not against each other in the present.

45:59 Dr. Timothy Morton, Philosopher and Author, 'Humankind':

45:59 Dr. Timothy Morton, Philosopher and Author, 'Humankind':

The trouble is not so much in what we're thinking about the world we live in, it's in terms of how we think about the world we live in.

46:11 Dr. Bruce Hood, Professor of Developmental Psychology, Author, 'The Self Illusion', University of Bristol, UK and Dr. Stephan Lewandowsky, Cognitive Scientist:

46:11 Dr. Bruce Hood, Professor of Developmental Psychology, Author, 'The Self Illusion', University of Bristol, UK and Dr. Stephan Lewandowsky, Cognitive Scientist:

Well here we have a human brain. When you see it in reality, it seems kind of a bit disappointing, doesn't it? It's very small for what it does, if you think about what we're capable of, and to think it all comes out of a little object like that it's quite remarkable.

46:30 Narrator:

Let's take a moment to imagine entering a theoretical world where everything in existence, at all scales, has equal value. From skyscrapers and trees, to humans, Cola, cups, and orangutans, shoes, and suitcases, vessels, water, diamonds, and dragonflies, even time itself. If we can imagine everything is intrinsically equal, then we'd know that what we perceive as reality comes from the value judgments that exist in our minds.

47:18 Dr. Timothy Morton, Philosopher and Author, 'Humankind':

47:18 Dr. Timothy Morton, Philosopher and Author, 'Humankind':

If everything exists in the same way, then we have an interesting problem. If it's true that even just by existing I am killing a huge number of lifeforms, then I have to figure out what kinds of lifeforms I'd like to kill and I have to be rather conscious and explicit about it, and being conscious and explicit about stuff is an incredible drag. There's always an unintended consequence of what you're doing, for example. Reality is happening on a number of different scales, all at once. You can never get it completely right. So, we're confronted again with the notion of exploring various different shades of hypocrisy.

48:04 Dr. Bruce Hood, Professor of Developmental Psychology, Author, 'The Self Illusion', University of Bristol, UK and Dr. Stephan Lewandowsky, Cognitive Scientist:

48:04 Dr. Bruce Hood, Professor of Developmental Psychology, Author, 'The Self Illusion', University of Bristol, UK and Dr. Stephan Lewandowsky, Cognitive Scientist:

You know the famous study about the $20 dollars I have, oh yeah, or I can give you $50 in a week's time, you've always, people just kind of almost compelled to go for the short term. To go for the short term, yeah, if you think about it, up to a point that's very rational, because you could be dead. That's right, you don't know... so the bird in the hand is worth two in the bush. Absolutely, so there is some rationality to that discounting.

48:26 Dr. Nathan Hagens, MBA Finance, PhD Natural Resources, Teaches 'Reality 101 – A Survey of the Human Predicament', University of Minnesota:

48:26 Dr. Nathan Hagens, MBA Finance, PhD Natural Resources, Teaches 'Reality 101 – A Survey of the Human Predicament', University of Minnesota:

Organisms that worried about 50 years from now were outcompeted by organisms that worried about 5 minutes from now.

48:38 Oren Lyons, Distinguished Professor of American Studies, Onondaga Council of Chiefs:

48:38 Oren Lyons, Distinguished Professor of American Studies, Onondaga Council of Chiefs:

Our fate is in our own hands. No one, no one else.

48:54 Narrator:

How will we shape the future towards a better outcome? What defines our identity? Are we our urges? Are we our principles? Who are we?

49:27 Dr. Ian Robertson, Cognitive Neuroscientist, Trinity College, University of Dublin:

49:27 Dr. Ian Robertson, Cognitive Neuroscientist, Trinity College, University of Dublin:

Who I am is really the accumulation of my experiences with other people, my interactions with other people. Babies don't have a self-concept, they don't have an idea of who they are. But as they interact with other people, they begin to create an image of themselves and a feeling of who they are, and thoughts about who they are. That's really picked up from the views and responses of other people.

50:01 Dr. Bruce Hood, Professor of Developmental Psychology, Author, 'The Self Illusion', University of Bristol, UK:

50:01 Dr. Bruce Hood, Professor of Developmental Psychology, Author, 'The Self Illusion', University of Bristol, UK:

In this modern society, people spend a large amount of time and effort accumulating objects and possessions and sometimes these have no particular use whatsoever. But it's almost as if we have to acquire things around us to make a statement of who we are. We use objects as an extension of our self.

50:19 Dr. Timothy Morton, Philosopher and Author, 'Humankind':

50:19 Dr. Timothy Morton, Philosopher and Author, 'Humankind':

In the life of sentient beings, desire is inevitable. The kind of plastic products that consumerism makes out of desire might be optional, but desire is inevitable.

50:32 Paul Roberts, Journalist, Author, 'The Impulse Society':

50:32 Paul Roberts, Journalist, Author, 'The Impulse Society':

That same drive is what makes it easy for Apple to sell us a new iPhone every year. I mean, I guarantee you, you don't need the next iPhone. You don't even know what new features it's going to have. And you won't know until you see them. But you're pretty sure you'll like them when you see them. And that was the whole point of this notion of dynamic obsolescence. You would be allowed to feel, to achieve a certain emotional state, for a short period of time, and then almost as quickly as you'd achieved it, it would begin fading, and you'd have to have something else. We have a real love for a way to feel how we want to feel, faster.

51:12 Dr. Leonard Mlodinow, Physicist, Author, 'Environmental Melancholia':

51:12 Dr. Leonard Mlodinow, Physicist, Author, 'Environmental Melancholia':

We may have a very developed conscious mind today with a lot of knowledge, cultural knowledge, technical knowledge, but the way we think is still very much influenced by a primitive unconscious that we developed millions of years ago.

51:35 Narrator:

We humans aren't just like animals, we are animals. And as animals, we compete for mates. Organisms in the wild that have extra resources to display like flashy tails, or large antlers are advertising to their mates that my genes are so good, I don't need to skimp and save, because, 'I'm so strong, I have these amazing attributes'. The same phenomenon happens in human societies to impress members of the opposite sex. A lot of these displays require spending extra energy and natural resources that we don't really need to be genetically fit. But we respond to those cultural signals, as if those things really do matter.

52:34 Dr. Bruce Hood, Professor of Developmental Psychology, Author, 'The Self Illusion', University of Bristol, UK and Dr. Ian Robertson, Cognitive Neuroscientist, Trinity College, University of Dublin:

52:34 Dr. Bruce Hood, Professor of Developmental Psychology, Author, 'The Self Illusion', University of Bristol, UK and Dr. Ian Robertson, Cognitive Neuroscientist, Trinity College, University of Dublin:

This question of status and of showing our status, I do believe that that's one of the most fundamental determinants of our behavior. Well, you know who knows this best of all is the marketers and advertising people. Because when they sell us stuff, and it's designer, or, what they're tapping into is this preoccupation with what other people think. Because they understand, intuitively, that we're all animals seeking social status.

53:05 Dr. Ruth Gates, Marine Biology, University of Hawaii at Manoa:

53:05 Dr. Ruth Gates, Marine Biology, University of Hawaii at Manoa:

We like things to be convenient, and, we like things to be new and we like bags that have names on it. We like to drink out of bottles that we can throw away. We like Styrofoam containers for our fast food. Plastic itself is something that is persistent through time. It gets recycled, it gets recycled, it gets smaller, it gets smaller, and now it's right back to us and detectable in our blood stream.

53:43 Dr. Renee Lertzman, Author, 'Environmental Melancholia':

53:43 Dr. Renee Lertzman, Author, 'Environmental Melancholia':

We are out of alignment with what we hear and we understand and we know what's going on, and the life that I am leading, including all the things I love, that might be really ecologically problematic, but that I love them anyways.

54:02 Dr. Bruce Hood, Professor of Developmental Psychology, Author, 'The Self Illusion', University of Bristol, UK:

54:02 Dr. Bruce Hood, Professor of Developmental Psychology, Author, 'The Self Illusion', University of Bristol, UK:

So, we have this very positive spin on ourself, and we try to maintain that characterization to the extent that we will only pay attention to information which confirms that bias. We'll deliberately reframe things that we've done in order to keep the coherence of who we are. Our brains are always creating these distortions. We have no direct contact with reality.

54:45 Dr. Leonard Mlodinow, Physicist, Author, 'Environmental Melancholia':

54:45 Dr. Leonard Mlodinow, Physicist, Author, 'Environmental Melancholia':

One of the important qualities that we developed that helped us survive was group identity. And today, group identity still plays an important role in our life. It has an important unconscious effect on our attitudes and our actions.

54:54 Dr. Bruce Hood, Professor of Developmental Psychology, Author, 'The Self Illusion', University of Bristol, UK:

54:54 Dr. Bruce Hood, Professor of Developmental Psychology, Author, 'The Self Illusion', University of Bristol, UK:

So, we have this tendency always rather than accepting it ourselves. And this is part of the bias which creates or keeps us this coherence of this being a 'good person'.

55:09 Narrator:

So, we're all capable of running around with the wrong idea of what is really going on in our world. And there's no mechanism or voice inside us to signal the artificiality of that. We don't want to live in a state of anxiety, we want to believe that the things we enjoy doing will never change. Do we confuse what we need with what we desire, and what we desire, with what we need?

55:43 Dr. Timothy Morton, Philosopher and Author, 'Humankind':

55:43 Dr. Timothy Morton, Philosopher and Author, 'Humankind':

Desire is logically prior to need, actually. And need is really, just, like stabilized desire that's been turned, probably socially, into something seemingly necessary. And so, I think we need to be a little bit careful when we talk about being in an ecological society, meaning our needs matching up with what we want.

56:04 Daniel Goleman, Psychologist, Science Journalist, Author, 'Emotional Intelligence':

56:04 Daniel Goleman, Psychologist, Science Journalist, Author, 'Emotional Intelligence':

So, there's this constant dance between the inhibitory centers that know what's good for us in the top of the brain, particularly the pre-frontal area, and the mid-brain areas for emotional impulse, which just wants to grab that yummy thing and have it now. So, let's say we're in a bakery. Everything looks so good, and our brain, which during evolution was designed to crave fat and sugar is going nuts. It just really wants one of those yummy things. But then, our pre-frontal cortex, the part of the brain that learns, the part of the brain that understands, says to us, 'You know, this is fattening, and you have that blood sugar problem, it's not so great for you'. And, the pre-frontal cortex has the ability to inhibit emotional impulse. And once we understand the true cost of the things we use and the things we do to the environment, the very same mechanism applies, and lets us pull back to the balcony of the mind, where we see everything is going on. Then we can make a better decision. This is the first step in changing our habits because without mindfulness, we don't even notice the choice points. We just blindly, spontaneously, automatically do that thing we've always done. Our old habits take us over.

57:26 Dr. Renee Lertzman, Author, 'Environmental Melancholia':

57:26 Dr. Renee Lertzman, Author, 'Environmental Melancholia':

When there's uncertainty, when there's a sense of precarity, when there's a feeling of vulnerability and confusion, that's exactly when we are most susceptible, obviously, to adhering to a message, a voice, a person who comes along and is able to meet those anxieties and those uncertainties with such confidence and certainty. And so, that's what we've seen replaying over and over again in politics. I don't need to mention the obvious examples of what happens when the, you know, larger public's sense of fear is coopted.

58:22 Wesley Clark, General, US Army (Ret.) Former NATO Supreme Allied Commander:

58:22 Wesley Clark, General, US Army (Ret.) Former NATO Supreme Allied Commander:

About half the wealth in the country is held by about 1% of the people and there are a lot of us out there, my parents were certainly one of them, who were scrambling from day to day to survive. And they, in their lifetimes, in the 1930s, had actually seen people starving because they couldn't earn a living. And so, most Americans haven't seen that, but some Americans still feel that way. And they feel the threat and the fear of unemployment, so they're focused near-term.

58:55 Dr. Timothy Morton, Philosopher and Author, 'Humankind':

58:55 Dr. Timothy Morton, Philosopher and Author, 'Humankind':

In any symbiotic relationship, who's on top and who's on bottom is a bit confusing and this could collapse at any moment.

59:06 Dr. Renee Lertzman, Author, 'Environmental Melancholia':

59:06 Dr. Renee Lertzman, Author, 'Environmental Melancholia':

The desire to be rescued is based on a profound and deep sense of powerlessness.

59:18 Dr. Timothy Morton, Philosopher and Author, 'Humankind':

59:18 Dr. Timothy Morton, Philosopher and Author, 'Humankind':

Open up a paper, or watch a conventional ecological documentary, and what you'll see are all kinds of facts designed to make you feel scared, and upset, and guilty. This is how we talk to ourselves about ecological disaster. Now the trouble is, that means that psychologically we're actually still putting ourselves before a time when it happened, somehow allowing ourselves the choice to go down that path or not. And the point is, we're already down the path.

59:50 Dr. Peirs Sellers, NASA Astronaut and Research Scientist, Goddard Space Flight Center:

59:50 Dr. Peirs Sellers, NASA Astronaut and Research Scientist, Goddard Space Flight Center:

When we, on the climate science side, talk about the reality of climate change, at first blush it sounds like a bit of a downer. So, one's natural reaction, if you hear bad news and someone else tells you, 'No, no, no, that's not true', is to at least, sort of say, hope that the guy that is telling you that this is not going to happen, is right.

1:00:11 Bob Inglis, Former Congressman (R) South Carolina, Executive Director Energy and Enterprise Initiative:

1:00:11 Bob Inglis, Former Congressman (R) South Carolina, Executive Director Energy and Enterprise Initiative:

For six years in congress, I said that climate change was nonsense, I really didn't know anything about it. Since I represented the reddest district in the reddest state in the nation, I knew that I needed to be opposed to it. And my son came to me. He was voting for the first time, and just turned 18, he said, 'Dad, I'll vote for ya, but you're going to clean up your act on the environment'. Your child is sick. Ninety-eight doctors say, 'Treat him this way'. Two say, 'No, this other is the way to go'. I'll go with the two. You're taking a big risk for those kids. Some people think that what we have here is an information deficit. That if we just gave people more scientific information, showed them the science, then they would come around. We've got people that make a living and a lot of money on talk radio and talk TV, pronouncing all kinds of things. They slept at Holiday Inn Express last night, and they are now experts on climate. It's an identification problem. It's, it doesn't look like my tribe, doesn't sound like my tribe, doesn't sound like our war cry, doesn't sound like our song. Too often it's presented, climate science is presented as if this is some kind of new religion, and you gotta believe. No, don't ask people to believe in climate science. Just say, 'Here's some data'. Now, what does your faith tradition tell you about what to do with that data? In mine, it tells me that I'm a steward of this glorious creation. Sometimes science turns out to be wrong. But other times it turns out to be very right. And the key to scientific endeavors, what we're here to discuss today, is openness, access to the data, and full challenging of the data. That's how we advance science.

1:02:18 Dr. Bruce Hood, Professor of Developmental Psychology, Author, 'The Self Illusion', University of Bristol, UK:

1:02:18 Dr. Bruce Hood, Professor of Developmental Psychology, Author, 'The Self Illusion', University of Bristol, UK:

There have been major revolutions in our thinking across civilization, for example, for thousands of years it was thought that the Earth was the center of the universe. We now know that that's not true. And then of course, there was also the idea the man is the pinnacle of the animal kingdom. But now we discover, through natural selection and Darwinism, that we are just one of a number of species that have existed. And finally, if you think about the self, the idea that we are individuals, in control of all our actions and behaviors that has been eroded away as we come to discover that this, in fact, is also not entirely true. So, I think that the science has revealed the arrogance of the individualism, the egocentrism that we have about our planet, our species, and ourselves, is unwarranted.

1:03:09 Narrator:

Ecology. It's a word derived from the Greek 'oikos', or 'household'. It's the study of the relationships that interlink all the members of the Earth's household. We can't think of ecology as only existing over there, beyond, because it has no boundaries and is in a state of constant flux. Ecology is intimate, coming right up to our skin, and through it. It's permeable, and borderless and chaotic. The internal and the external are always entwined. So, when we speak about sustainability, what is it that we hope to sustain?

1:04:20 Dr. Timothy Morton, Philosopher and Author, 'Humankind':

1:04:20 Dr. Timothy Morton, Philosopher and Author, 'Humankind':

One of the problems with philosophy is that it isn't just in your head. Philosophy is everywhere. Everything, in a way, was a dream in someone's head, in built space. Thought isn't just something that's in here, thought is everywhere.

1:04:41 Dr. Rich Pancost, Professor of Biogeochemistry, Director Cabot Institute, University of Bristol, UK:

1:04:41 Dr. Rich Pancost, Professor of Biogeochemistry, Director Cabot Institute, University of Bristol, UK:

The story that we live in right now is that we grow the economy by consuming goods and in particular, consuming goods that exist in limited quantities.

1:04:54 Dr. Renee Lertzman, Author, 'Environmental Melancholia':

1:04:54 Dr. Renee Lertzman, Author, 'Environmental Melancholia':

We have the tendency as meaning-making, story-making people, creatures, to have characters, to have protagonists who are the villains, and who are the heroes and the rescuers, and that's deep in our human psyche, and that's how we tend to make sense of the world. And the tendency, very understandably, is to create villains, such as corporations or oil industries, and to create heroes, the eco-warriors. While that's understandable, what it's actually doing is it's creating a bit of an exemption story where we as individuals are somewhat exempt or somewhat out of the story.

1:05:50 Dr. Nathan Hagens, MBA Finance, PhD Natural Resources, Teaches 'Reality 101 – A Survey of the Human Predicament', University of Minnesota:

1:05:50 Dr. Nathan Hagens, MBA Finance, PhD Natural Resources, Teaches 'Reality 101 – A Survey of the Human Predicament', University of Minnesota:

There's a lot of criticism in our culture right now that capitalism is bad, and that without capitalism we wouldn't be impacting things. And that's partially true.

1:06:08 Narrator:

Underpinning this system is the optimal foraging instinct that resides in our animal natures. Wolves, for instance, they're better off running down an elk than spending the same amount of time and energy chasing a mouse, or a rabbit. They're more evolutionarily fit and have more calories to raise their offspring. The same dynamic is in humans. We like to invest a little and get more in return. We do this in stock markets, when we get a 20% discount on shoes, a two-for-one cocktail at happy hour, or a steal of a deal buying a house on some special foreclosure. Capitalism isn't entirely good or bad. Capitalism is in service of the superorganism. Together we're functioning like a gigantic wolf pack, hungry for more energy.

1:07:21 Bob Inglis, Former Congressman (R) South Carolina, Executive Director Energy and Enterprise Initiative:

1:07:21 Bob Inglis, Former Congressman (R) South Carolina, Executive Director Energy and Enterprise Initiative:

One of the many causes of war is actually the shortage of energy.

1:07:33 Dr. Timothy Morton, Philosopher and Author, 'Humankind':

1:07:33 Dr. Timothy Morton, Philosopher and Author, 'Humankind':

Energy is always flowing from a kind of compacted state to a less compacted state. Entropy is how things are constantly running down to zero. We can't actually create a machine that reverses entropy. Entropy is why time seems to only be going in one direction. Entropy is why you've never seen a broken glass reassemble as a perfect glass. And if you're looking for the perfect ecological machine that will actually, fully put the energy back into the system that the machine has sucked out of it, I'm afraid you're going to be waiting until after the end of the universe.

1:08:25 Dr. Mark Plotkin, Ethnobotanist, Amazon Conservation Team:

1:08:25 Dr. Mark Plotkin, Ethnobotanist, Amazon Conservation Team:

So, you always have to leave room in your analysis of animals, and animals in the broad sense - I include people in that, of thinking that we're always going to do the right thing, that we've optimized all of our actions, our foraging strategies and everything else, and we can extrapolate from there because if we had everything right, there wouldn't be any problems, would there. There'd be no poverty, there'd be no climate change, there'd be no warfare.

1:08:55 Bob Inglis, Former Congressman (R) South Carolina, Executive Director Energy and Enterprise Initiative:

1:08:55 Bob Inglis, Former Congressman (R) South Carolina, Executive Director Energy and Enterprise Initiative:

Where you sit determines where you stand, and if you're if you're sort of all tied up in a particular kind of industry and you see your future there, naturally you hold on.

1:09:11 Wesley Clark, General, US Army (Ret.) Former NATO Supreme Allied Commander:

1:09:11 Wesley Clark, General, US Army (Ret.) Former NATO Supreme Allied Commander:

There's no such thing as a free market. I hope people can understand that, because if there were free markets, you'd end up the way we ended up in the late 1800s, with a few very powerful trusts controlling all of America. Without government helping us shape the market forces, the market forces will be taken by the very short-term requirements that are placed on them by us. By our need to go to the filling station and get the cheapest fuel. By the need for the pension fund to get its 8% return, no matter what it's investing in. Really tough to earn the six or seven percent, or eight percent, per year that were in those actuarial calculations when the pension funds were established. So, it's not some foreign institution that makes us be short-term focused, it's us.

1:10:10 White House Reporter - 1973:

Why didn't the administration anticipate the energy crisis several years ago? Or formulate a positive action plan to do something about it?

1:10:21 Wesley Clark, General, US Army (Ret.) Former NATO Supreme Allied Commander:

1:10:21 Wesley Clark, General, US Army (Ret.) Former NATO Supreme Allied Commander:

We have to bring a different perspective to this. A couple of years ago, I asked a member of congress. I said, 'What's the toughest issue you're dealing with? Right now?' And she said, 'Federal subsidies for seashore flood insurance, because we've always subsidized it, and the cost of the subsidies is going way up, and people insist on buying these homes that are subject to tidal erosion and to flooding, and to destruction, ultimately'.

1:10:52 Bob Inglis, Former Congressman (R) South Carolina, Executive Director Energy and Enterprise Initiative:

1:10:52 Bob Inglis, Former Congressman (R) South Carolina, Executive Director Energy and Enterprise Initiative:

There isn't transparent accountable pricing for all the impacts of the burning of fossil fuels. The markets aren't working right. And once those costs are revealed, and put at the meter, and put on the pump, then consumers will make choices that are in their self interest. We'll be making transportation fuel on our roofs. Of course, I'm not saying that we get to Nirvana and we don't have any war. One of the causes of war would be less, because energy would be more abundantly available and more distributed around the world.

1:11:33 Narrator: